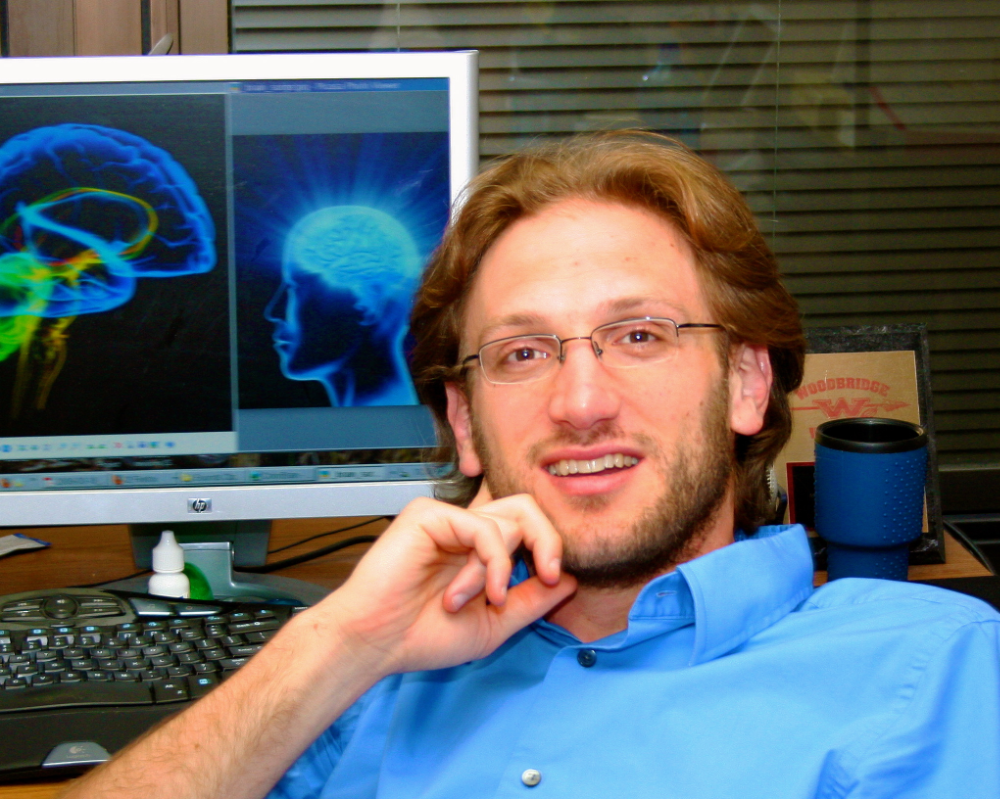

Justin Feinstein, Ph.D.

Clinical Neuropsychologist

Dr. Feinstein is an expert in the neuroscience of fear who is trailblazing a new path forward for the treatment of anxiety. Utilizing both the lesion method and functional neuroimaging, his research has revealed important clues about the role of the human amygdala and insula in the conscious experience of fear and anxiety. He has over 50 peer-reviewed publications in some of the top scientific journals and his research has been featured in the popular press including the New York Times, NPR, TIME magazine, and CBS National News.

His current work is focused on studying the intimate connection between the body & the brain, and developing new technologies to help bring this connection to the forefront of awareness. As part of these efforts, his research has laid the foundation for novel therapies that can naturally alleviate stress and anxiety without the use of drugs including Floatation-REST (Reduced Environmental Stimulation Therapy) and the modulation of CO2 as a form of interoceptive exposure therapy. In 2021, Dr. Feinstein became President and Director of the Float Research Collective, a nonprofit organization that is playing a pivotal role in establishing Floatation-REST as an accepted medical treatment.

Dr. Feinstein received his Ph.D. in Clinical Neuropsychology from the University of Iowa and completed his postdoctoral fellowship at the California Institute of Technology. He earned his undergraduate degree in Cognitive Neuroscience at the University of California San Diego, where he later returned to complete his clinical internship at the San Diego VA hospital with a focus on the treatment of veterans with PTSD using prolonged exposure therapy. Dr. Feinstein is an adjunct professor in the Department of Neurology at the University of Iowa. Between 2013-2020, he was also a professor in the Oxley College of Health Sciences at the University of Tulsa, as well as the founder and director of the Float Clinic & Research Center at the Laureate Institute for Brain Research where he spearheaded the first studies to show how floating could rapidly and reliably ease the suffering in patients with anxiety and stress-related disorders.

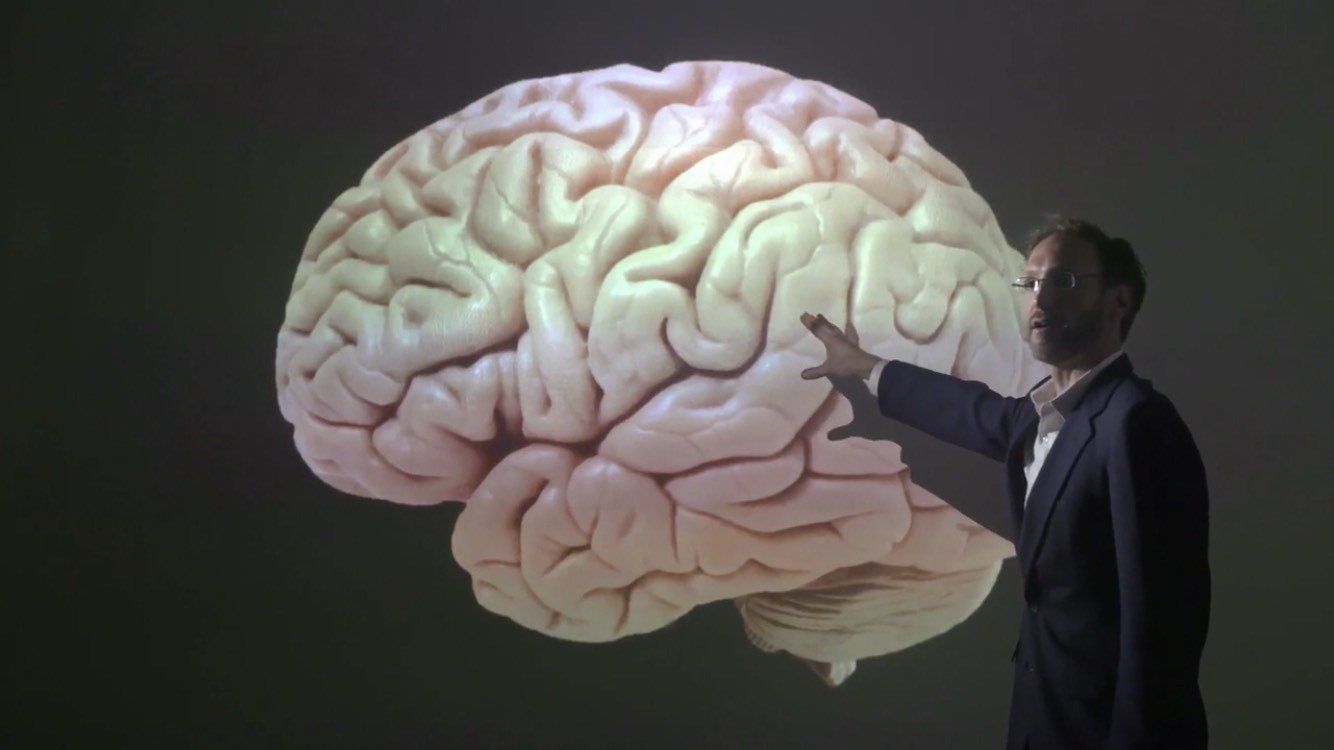

Exploring the origins of fear and anxiety in the human brain

Understanding the brain systems that instantiate our experience of fear and anxiety has been a primary focus of Dr. Feinstein’s research. He was part of the team that completed the first dose-response pharmaco-fMRI study to examine how the human brain responds to the benzodiazepine Lorazepam. Using a double-blinded, placebo-controlled design, they discovered that activation in both the amygdala and insula was reduced in a dose-dependent manner following administration of the anti-anxiety medication. In a separate fMRI study, they found that subjects with high levels of trait anxiety demonstrated the opposite pattern, showing heightened levels of activation in both the amygdala and insula. Since fMRI is a fundamentally correlative technique, Dr. Feinstein focused his doctoral studies on exploring the causal role of the amygdala and insula in relation to fear and anxiety. Several in-depth case studies have emerged from this line of research, including the case of Patient SM, a woman with circumscribed bilateral amygdala damage who has become one of the most renowned lesion cases in the history of neuropsychology. SM has a deficit in her expression and experience of fear in response to external threats. In stark contrast, her fear response to internal threats, such as inhaling an air mixture containing 35% carbon dioxide (CO2), was appreciably heightened, to the point of inducing panic attacks. Thus, there appears to be an important neural distinction between threats conveyed through exteroceptive sensory channels (e.g., visual and auditory pathways) versus threats conveyed through interoceptive sensory channels (e.g., acid-activated chemoreceptors stimulated by rising levels of CO2). Whereas the amygdala may be critical for the generation of exteroceptive fear, it does not appear to be necessary for interoceptive fear and may instead play a pivotal role in the inhibition of panic. Follow-up studies are now investigating the neural systems supporting interoceptive fear, as well as studying the effects of using CO2 as a form of interoceptive exposure aimed at reducing anxiety sensitivity.

Developing novel approaches to study and treat interoceptive fear

Key to understanding interoceptive fear is the development of novel approaches that can safely and reliably enhance awareness for cardiorespiratory sensations – the primary driver of interoceptive fear. In addition to studying various forms of CO2 modulation, Dr. Feinstein and his close collaborator, Dr. Sahib Khalsa, have employed isoproterenol, a rapid-acting peripheral β-adrenergic agonist akin to adrenaline. Through intravenous administration of isoproterenol to rare lesion patients, as well as patients with high levels of anxiety sensitivity undergoing functional neuroimaging, they have begun to parse the neural systems of cardiorespiratory awareness. Since most interoceptive perturbations entail sympathetically-mediated autonomic changes, Dr. Feinstein and Dr. Khalsa have also taken a deep dive into the other end of the autonomic spectrum by studying Floatation-REST (Reduced Environmental Stimulation Therapy), a novel intervention that allows the nervous system to enter a relaxed/parasympathetic physiological state by systematically reducing sensory stimulation from the external world. They recently received the first NIH-funded grant to explore Floatation-REST and have several ongoing clinical trials examining the long-term effects of floating in anxious populations. Their research has shown that Floatation-REST is not a form of sensory deprivation (a common misnomer), but instead, the float environment actually enhances one’s awareness for cardiorespiratory sensations. The practice of mindful meditation is often predicated on focusing one’s full attention and awareness on present moment sensations such as the breath, and consequently, the float environment was found to spontaneously induce states of mindfulness, including in anxious patients who often have great difficulty meditating. Moreover, the float environment appeared to weaken the bond between cardiorespiratory sensations and anxiety, especially when such sensations were experienced against a backdrop of reduced muscle tension and physiological relaxation. This form of reciprocal inhibition has the potential to greatly reduce anxiety sensitivity and help anxious patients (including those with PTSD) form a new association in their brain, one that links the experience of cardiorespiratory sensations with a state of relaxation instead of anxiety.

Understanding the temporal dynamics of emotion and feeling

Starting with his first publication, Dr. Feinstein has been interested in understanding the temporal dynamics of emotional processing in the human brain, especially as it relates to habituation and the recovery of emotion. As part of this program of research, he asked the following question: Can the experience of an emotion persist once the memory for what induced that emotion has been forgotten? In order to answer this question, he studied a rare group of patients with severe anterograde amnesia following circumscribed bilateral damage to the hippocampus. The results revealed a striking dissociation between the conscious awareness of an emotional state and the conscious recollection for that state’s origin. Even though the amnesic patients could no longer remember watching a series of emotional film clips when queried 5 minutes after they were over, the induced feelings of emotion persevered for over 30 minutes. These findings suggest that the brain is organized in such a way that a feeling of emotion can persist without any explicit memory for its cause. Quite strikingly, the feeling of sadness persisted longer in the amnesic patients than the comparison subjects (whose memory for the film clips was entirely intact). The findings have since been replicated in patients with Alzheimer's disease and have important implications for how society treats individuals with memory disorders, as events that have long been forgotten could continue to induce suffering or well-being. Following up on this line of research, Dr. Feinstein’s doctoral dissertation explored the brain regions necessary for holding onto an emotional state. In a large sample of lesion patients with damage to different regions of the limbic and paralimbic system, it was discovered that patients with bilateral damage affecting both the amygdala and insula experienced extremely transient states of emotion that would rapidly dissipate within a minute. This research suggests that the amygdala and insula play a critical role in holding onto states of emotion, while the ventromedial prefrontal cortex and hippocampus serve to regulate these states. Importantly, dysfunction within this larger circuitry may contribute to the prolonged periods of emotional suffering inherent to conditions like anxiety and depression.

Dr. Feinstein’s Curriculum Vitae

List of Services

-

The elicitation of relaxation and interoceptive awareness using floatation therapy in individuals with high anxiety sensitivity.LINK List Item 1

Biological Psychiatry: Cognitive Neuroscience and Neuroimaging, 3, 555-562. Feinstein JS, Khalsa SS, Yeh H, Al Zoubi O, Arevian AC, Wohlrab C, Pantino MK, Cartmell LJ, Simmons WK, Stein MB, & Paulus MP (2018).

-

Examining the short-term anxiolytic and antidepressant effect of Floatation-REST.LINK List Item 2

PLoS ONE, 13, e0190292. Feinstein JS, Khalsa SS, Yeh H, Wohlrab C, Simmons WK, Stein MB, & Paulus MP (2018).

-

The human amygdala and the induction and experience of fear.LINK List Item 3

Current Biology, 21, 34-38. Feinstein JS, Adolphs R, Damasio A, & Tranel D (2011).

-

Fear and panic in humans with bilateral amygdala damage.LINK List Item 4

Nature Neuroscience, 16, 270-272. Feinstein JS, Buzza C, Hurlemann R, Follmer RL, Dahdaleh NS, Coryell WH, Welsh MJ, Tranel D, & Wemmie JA (2013).

-

A tale of survival from the world of Patient SM.LINK

Living Without an Amygdala, Guilford Press, 1-38. Feinstein, JS, Adolphs, R, & Tranel, D (2016).

-

Panic anxiety in humans with bilateral amygdala lesions: Pharmacological induction via cardiorespiratory interoceptive pathways.LINK

Journal of Neuroscience, 36, 3559-3566. Khalsa SS, Feinstein JS, Wi L, Feusner JD, Adolphs R, & Hurlemann R (2016).

-

The insular cortex dynamically maps changes in cardiorespiratory interoception.LINK

Neuropsychopharmacology 43, 426-434. Hassanpour MS, Simmons WK, Feinstein JS, Luo Q, Lapidus RC, Bodurka J, Paulus MP, & Khalsa SS (2018).

-

Association of generalized anxiety disorder with autonomic hypersensitivity and blunted ventromedial prefrontal cortex activity during peripheral adrenergic stimulation.Item Link

JAMA Psychiatry, 79, 323-332. Teed AR, Feinstein JS, Puhl M, Lapidus RC, Upshaw V, Kuplicki RT, Bodurka J, Ajijola OA, Kaye W, Thompson WK, Paulus MP, & Khalsa SS (2022).

-

Oxytocin-enforced norm compliance reduces xenophobic outgroup rejection.LINK

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 114, 9314-9319. Marsh N, Scheele D, Feinstein JS, Gerhardt H, Strang S, Maier W, & Hurlemann R (2017).

-

Sustained experience of emotion after loss of memory in patients with amnesia.LINK

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107, 7674-7679. Feinstein JS, Duff MC, & Tranel D (2010).

-

Feelings without memory in Alzheimer Disease.LINK

Cognitive and Behavioral Neurology, 27, 117-129. Guzman-Velez E, Feinstein JS, & Tranel D (2014).

List of Services

-

Amygdala-driven apnea and the chemoreceptive origin of anxiety.Item Link

Biological Psychology, 170, 108305. Feinstein JS, Gould D, & Khalsa SS (2022).

-

Lesion studies of human emotion and feeling.LINK List Item 1

Current Opinion in Neurobiology, 23, 304-309. Feinstein JS (2013).

-

Bilateral limbic system destruction in man.LINK List Item 2

Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology, 32, 88-106. Feinstein JS, Rudrauf D, Khalsa SS, Cassell MD, Bruss J, Grabowski TJ, & Tranel D (2010).

-

Preserved emotional awareness of pain in a patient with extensive bilateral damage to the insula, anterior cingulate, and amygdala.LINK List Item 3

Brain Structure and Function, 221, 1499-1511. Feinstein JS, Khalsa SS, Salomons TV, Prkachin KM, Frey-Law LA, Lee JE, Tranel D, & Rudrauf D (2016).

-

Dose-dependent decrease of activation in bilateral amygdala and insula by lorazepam during emotion processing.LINK List Item 4

Archives of General Psychiatry, 62, 282-288. Paulus MP, Feinstein JS, Castillo G, Simmons AN, & Stein MB (2005).

-

Increased amygdala and insula activation during emotion processing in anxiety-prone subjects.LINK

The American Journal of Psychiatry, 164, 318-327. Stein MB, Simmons A, Feinstein JS, & Paulus MP (2007).

-

Anterior insula reactivity during certain decisions is associated with neuroticism.LINK

Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 1, 136-142. Feinstein JS, Stein MB, & Paulus MP (2006).

-

An active inference approach to interoceptive psychopathology.LINK

Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 15, 97-122. Paulus MP, Feinstein JS, & Khalsa SS (2019).

-

The somatic error hypothesis of anxiety.LINK

The Interoceptive Mind, Oxford University Press, 144-164. Khalsa SS & Feinstein JS (2019).

-

The pathways of interoceptive awareness.LINK

Nature Neuroscience, 12, 1494-1496. Khalsa SS, Rudrauf D, Feinstein JS, & Tranel D (2009).

-

Interoception and mental health: a roadmap.LINK

Biological Psychiatry: Cognitive Neuroscience and Neuroimaging, 3, 501-513. Khalsa SS, Adolphs R, Cameron OG, Critchley HD, Davenport PW, Feinstein JS, Feusner JD, Garfinkel SN, Lane RD, Mehling WE, Meuret AE, Nemeroff CB, Oppenheimer S, Petzschner FH, Pollatos O, Rhudy JL, Schramm LP, Simmons WK, Stein MB, Stephan KE, Van Den Bergh O, Van Diest I, von Leupoldt A, Paulus MP, and the Interoception Summit 2016 participants (2018).

Selected Press

Justin Feinstein, Ph.D.

List of Services

-

CBS NATIONAL NEWSLINK List Item 1

APRIL 2018

-

DISCOVER MAGAZINELINK List Item 2

APRIL 2010

-

DISCOVER MAGAZINEItem Link List Item 3

DEC 2010

-

GLOBE AND MAILItem Link List Item 4

JULY 2016

-

HAARETZItem Link

APRIL 2012

-

HARPER’S MAGAZINEItem Link

MARCH 2011

-

HEALTH.COMItem Link

APRIL 2016

-

LIVE HAPPYItem Link

APRIL 2016

-

NATIONAL PUBLIC RADIO (NPR)Item Link

APRIL 2010

-

NATIONAL PUBLIC RADIO (NPR)Item Link

FEB 2013

-

NATIONAL PUBLIC RADIO (NPR)Item Link

OCT 2017

List of Services

-

NBC TODAY SHOWItem Link List Item 1

MAY 2011

-

NEW SCIENTISTItem Link List Item 2

cover story for issue 2907

MARCH 2013

-

NEW YORK TIMESItem Link List Item 3

DEC 2010

-

NEW YORK TIMESItem Link List Item 4

DEC 2010

-

NEW YORK TIMESItem Link

JAN 2011

-

OKLAHOMA NEWS REPORT (OETA)Item Link

JAN 2018

-

PSYCHOLOGY TODAYItem Link

FEB 2013

-

SCIENTIFIC AMERICANItem Link

MAY 2011

-

SCIENTIFIC AMERICANItem Link

APRIL 2010

-

THE GUARDIANItem Link

MARCH 2016

List of Services

-

THE NATURE OF THINGSItem Link

Episode on the Science of Fear

OCT 2019

-

THIS LAND PRESSItem Link List Item 1

JAN 2016

-

TIME MAGAZINEItem Link List Item 2

NOV 2015

-

TIME MAGAZINEItem Link List Item 3

DEC 2010

-

TIME MAGAZINEItem Link List Item 4

Special issue on Mental Health

OCT 2018

-

TULSA WORLDItem Link

JAN 2017

-

TULSA WORLDItem Link

FEB 2018

-

USA TODAYItem Link

DEC 2010

-

VICEItem Link

OCT 2015

-

VICEItem Link

AUG 2017

Dr. Feinstein’s research has also been featured in the following books

Contact

Justin Feinstein, Ph.D.

Dr. Feinstein’s research presentations are available to view online here.

Contact Dr. Feinstein

Thank you for contacting me. I will get back to you as soon as possible.

Please try again later

FIND A FLOAT CENTER

If you are looking for somewhere to try floating,

please click on the Float Center Map link below to find a center near you.

The Float Center map is not managed by us, but if you are a float center owner or customer, and your center is not listed on the map, please complete this quick form to apply to be added.

ABOUT US

The official site dedicated to the medical use of clinical floatation therapy.

Published peer reviewed papers, presentations and news related to Clinical Floatation to assist researchers and clinicians in all disciplines

FLOAT RESEARCH COLLECTIVE

Find out about the Float Research Collective and how you could get involved....

KEEP INFORMED

Keep updated with the latest news, publications and presentations, the resource for everyone interested in the science of Floatation-REST. Sign up to our newsletter here: (opens a new window)

CONTACT US TO FIND OUT MORE

Contact Us

Thank you for contacting Clinical Floatation.

We will get back to you as soon as possible

Please try again later